Il est difficile de discuter de la lutte contre la pauvreté sans aborder la question du logement abordable. L'accès à un logement adéquat et abordable est essentiel pour construire une vie stable et sans pauvreté.

L'accès ou non à un logement abordable peut avoir un impact direct sur l'état de santé d'une personne. la santé Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtrecapacité à acquérir et conserver un emploi Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtreet même leur interactions avec le système judiciaire Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre. Pour les familles, cela peut avoir un impact sur la vie de tous les jours. la croissance et le développement de l'enfant Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtreLes coûts liés à l'éducation, à la santé et à l'environnement ont une incidence sur les résultats scolaires et rendent difficile l'accès aux autres nécessités, telles que le chauffage et l'électricité, la nourriture, les soins personnels et le transport.

Malgré son importance, il est de plus en plus difficile pour les Ontariens de trouver un logement abordable. Entre 2012 et 2016, le le prix moyen des logements en Ontario a augmenté de 18 Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre pour cent, et le le loyer moyen d'un appartement de deux chambres a augmenté de 12 Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre pour cent.

La capacité à payer ce logement n'a pas augmenté aussi rapidement : entre 2011 et 2015, les le revenu médian en Ontario n'a augmenté que de 7,5 Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre pour cent. Les logements du marché devenant de moins en moins abordables, la liste d'attente pour les logements à loyer indexé sur les revenus (logements dont le loyer est fixé à un pourcentage abordable des revenus du ménage) s'est allongée : 171 360 ménages étaient sur liste d'attente en 2015 Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre, en hausse de 9 % depuis 2011.

De nombreuses théories expliquent la flambée des prix de l'immobilier, les deux principaux responsables étant le manque d'infrastructures et de services. de l'offre Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre (en raison de réglementation en matière d'utilisation des sols Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre(restrictions de zonage obsolètes ne permettant pas la densité, formalités administratives excessives augmentant les coûts pour les promoteurs et manque d'infrastructures adaptées), et une forte augmentation de l'offre de produits et de services de qualité. en demande Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre (acheteurs étrangers, investissements spéculatifs et faibles taux d'intérêt).

L'augmentation des prix du logement a un effet d'entraînement sur le coût des loyers, les personnes n'ayant pas les moyens d'acheter un logement. se tourner vers la location Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre. Pourtant, la construction de logements locatifs construits à cet effet, tels que les immeubles d'appartements (par opposition aux appartements en copropriété ou aux maisons louées par le propriétaire), est restée au point mort pendant quatre décennies. Bien qu'il y ait eu une la résurgence récente des locations à des fins spécifiques Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtreil faudra beaucoup de temps pour rattraper la demande. Cette situation est particulièrement préoccupante pour les ménages à faibles revenus, car ils ne sont pas en mesure d'accéder à l'électricité. deux tiers d'entre eux louent leur logement Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre.

Les logements à loyer indexé sur le revenu (également connus sous le nom de logements sociaux) constituent la dernière étape du continuum du logement avant les refuges et les logements supervisés, mais il n'y en a tout simplement pas assez pour répondre à la demande. Entre le milieu des années 60 et le début des années 90, les gouvernements fédéral et provinciaux ont construit plus de 200 000 logements sociaux en Ontario Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre. Cependant, en 1996, les deux gouvernements ont cessé de financer la construction de nouveaux logements sociaux et rien n'a été construit jusqu'en 2000.

Depuis lors, la plupart des responsabilités en matière d'administration, de construction et d'entretien des logements sociaux ont été confiées à la Commission européenne. transférés aux gouvernements municipaux Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtrequi ont beaucoup moins de possibilités de lever des fonds par le biais de l'impôt. Bien que les gouvernements provincial et fédéral aient accordé un certain financement aux organismes municipaux par l'intermédiaire de la Programme d'investissement dans le logement abordable (IAH) Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtremais c'est loin d'être suffisant.

L'IAH ne financera que la création et la réparation de 11 000 logements sociaux entre 2014 et 2020, mais on estime qu'il faudrait construire 10 000 unités supplémentaires chaque année pour répondre à la demande Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre. Les agences municipales telles que la Toronto Community Housing Corporation (TCHC) sont en grande difficulté, estimant que d'ici 2023 Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtreEn effet, les trois quarts des logements existants seront en mauvais état ou dans un état critique, et 7 500 logements devront tout simplement être fermés. L'impact de cette mesure sur les personnes inscrites sur la liste d'attente de Toronto, qui dure depuis dix ans, sera profond.

La Société canadienne d'hypothèques et de logement (SCHL) définit les "besoins impérieux de logement" comme le fait de consacrer plus de 30 % de son revenu au logement ou de vivre dans un logement en mauvais état ou trop petit. 13 % des Ontariens relèvent de cette catégorie. Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre. Au rythme actuel, il faudrait 73 ans pour éliminer les besoins impérieux de logement Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre en Ontario.

Ces tendances sont extrêmement préoccupantes pour les banques alimentaires de l'Ontario. En effet, avec 90 % des clients des banques alimentaires vivent dans des logements locatifs ou sociaux Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtreCes pénuries de logements et ces hausses de loyers ont un impact énorme sur eux. Le client moyen d'une banque alimentaire dépense 70 % de leur revenu pour le logement Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtreCe qui les expose à un risque élevé de sans-abrisme. Selon notre étude, après avoir payé le logement et les services publics, 45 % des clients des banques alimentaires n'ont plus que $100, ce qui leur laisse peu d'argent pour les besoins essentiels tels que la nourriture, le transport et les médicaments.

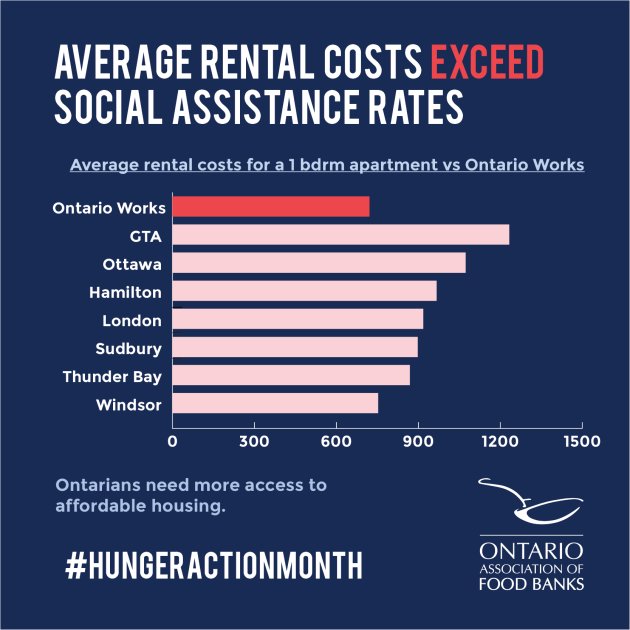

La principale source de revenu des deux tiers des clients des banques alimentaires est le programme Ontario au travail (OT) ou le Programme ontarien de soutien aux personnes handicapées (POSPH). Le coût élevé du logement signifie que le maigre montant qu'ils reçoivent doit être étiré encore plus. Le montant total que reçoit une personne seule bénéficiant d'OT - $721 par mois - est inférieur à la somme de 1,5 million d'euros. coût moyen d'un appartement d'une chambre Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre dans la plupart des grandes villes de l'Ontario.

Avec de telles statistiques, il n'est pas surprenant que tant de personnes aient besoin de recourir aux banques alimentaires. Dans notre Rapport sur la faim 2016 Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtreDans le cadre de l'enquête sur les banques alimentaires, nous avons constaté que l'utilisation des banques alimentaires en Ontario a augmenté de 6,9 % depuis 2008. À Toronto, où le coût du logement est l'un des plus élevés du pays, la Daily Bread Food Bank a enregistré une augmentation de 24 % entre 2008 et 2017, comme l'indique son dernier rapport sur les banques alimentaires. Rapport sur les personnes qui ont faim Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre.

Le logement est la dépense la plus importante pour la plupart des gens, et c'est un coût non négociable. Vous devez payer à votre propriétaire la totalité de votre loyer chaque mois, sous peine d'être expulsé et de vous retrouver à la rue. Pour pouvoir payer leur loyer, les gens réduisent souvent leurs dépenses essentielles, comme la nourriture, le chauffage ou l'électricité. Heureusement, les banques alimentaires sont là pour vous aider.

C'est pourquoi l'Association des banques alimentaires de l'Ontario soutient un projet de loi sur les banques alimentaires. allocation de logement transférable Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre. Cette allocation serait versée directement au locataire et garantirait que son loyer ne dépasse pas 30 % de ses revenus. Elle serait destinée aux bénéficiaires de l'aide sociale et aux travailleurs pauvres qui n'ont pas les moyens de payer leur loyer.

Une allocation de logement transférable permet aux personnes de rester chez elles au lieu de devoir déménager dans un nouveau logement, ce qui stabilise les communautés existantes. La plupart des ménages ont un besoin impérieux de logement depuis moins de deux ans Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre. Cette allocation de logement transférable offrirait un plus grand choix et une plus grande flexibilité, tout en réduisant la nécessité de construire des logements sociaux.

Nous sommes prudemment optimistes quant aux chances de mise en œuvre d'un tel programme. Actuellement, le gouvernement provincial met à l'essai une allocation de logement transférable pour les survivants de la violence domestique et prévoit d'engager des consultations au sujet d'un programme d'allocation de logement transférable pour les survivants de la violence domestique. cadre pour une allocation de logement transférable Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre.

Il existe également un proposition présentée par le Collectif national pour le logement Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre - qui comprend notre membre, la Daily Bread Food Bank - d'inclure dans la prochaine stratégie nationale pour le logement une allocation de logement transférable unique, harmonisée et cofinancée par les gouvernements fédéral, provinciaux et territoriaux pour tous les Canadiens admissibles.

Nous constatons que la tendance de l'utilisation des banques alimentaires va dans le mauvais sens - à la hausse, plutôt qu'à la baisse. Si, en tant que société, nous voulons sérieusement réduire la faim et la pauvreté, nous devons nous attaquer à la crise du logement abordable, qui est le principal facteur de stress pour les budgets des Ontariens à faible revenu. Avec un gouvernement provincial et un gouvernement fédéral qui ont tous deux déclaré leur engagement à réduire la pauvreté, nous sommes à un moment idéal pour introduire une prestation de logement qui fait une différence dans la vie des familles qui luttent pour joindre les deux bouts chaque mois.

Si vous êtes en faveur d'une allocation de logement transférable, contactez votre député fédéral ou provincial et faites-le leur savoir ! Tweetez sur la nécessité d'une allocation de logement transférable en utilisant le hashtag #LetsTalkHousing. Pour plus d'informations sur la façon dont vous pouvez agir contre la faim, veuillez consulter les sites suivants www.oafb.ca/hunger-action-month Le lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre